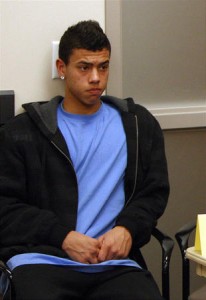

- Photo courtesy Tom Smart, Deseret News

43 percent of Utah’s foster-care population is teens, but only a few families take in older youths

By Sara Israelsen-Hartley

Deseret News

Published: Sunday, Feb. 6, 2011

SOUTH JORDAN — Each morning after his dad died, 14-year-old Ecum would wake up his siblings, get them dressed and ready for school and search for breakfast. “I was being the dad,” said Ecum, now 16. “It was pretty hard, being something I didn’t know I was going to be. It was hard and a big step.”

Eventually the state placed Ecum and several of his siblings in foster care, where they waited for a sense of stability that had disappeared from their lives. The teen still remembers the call from his caseworker and the first time he met his future adoptive parents, Rob and Kim Gerlach.

“They showed me my ideal family,” Ecum told a group of current and potential foster parents during a recent panel discussion. “I’d drawn it on a piece of paper and I got exactly what I wanted. I found two of the greatest people. I love them a ton.”

It was quiet for a moment as he finished, and then a man in the back piped up, “Can we have him?”

“Taken!” Kim Gerlach responded quickly, wiping tears from her eyes.

Talking about foster teens

The panel discussion, sponsored by the Utah Foster Care Foundation, allowed several teens and their foster parents, including Ecum and the Gerlachs, a chance to answer questions and educate potential foster parents about what it’s like to open up their hearts and homes to teenagers.

Currently, Utah has close to 1,230 teens in foster care — about 43 percent of the foster care population; however, a recent state audit among the state’s 1,298 licensed foster care families found that only 198 families were willing to foster 14- to 18-year-olds, which means the rest of the teens are placed in group or proctor home with trained staff and often without siblings.

Yet most of the foster parents on the panel said they prefer taking older children, including Marcus and Doe Corrin, who specifically request teenage girls, after realizing that babies weren’t the best match for them.

“I had an infant in my house and we were all crying at 3 a.m.,” Doe Corrin said. “I’d rather have girls’ night, do hair, nails, make-up than change a diaper any day.”

Unlike babies or toddlers, teens are much more self-sufficient, more able to communicate and seem to have an easier time “sharing” mom and dad, said Michelle Ostmark, a mother of seven — three biological and four adopted through DCFS. She and her husband, Adam, have fostered nearly 80 children over seven years.

“Even on bad days I enjoy (teens) more than the younger kids,” she said.

During the panel, the moderator brought up commonly asked questions, including “Do we take our foster child to his original school?” (most parents said they try to keep as much stability in the child’s life, even if it means a few months of driving out of their way to stay at the same school) and, “I’ve never dealt with teenagers, do I have the skills to help them?”

“You don’t,” Rob Gerlach responded quickly, with a smile.

Kim Gerlach went on to explain that their adopted baby girl was two when Ecum came into their lives, yet he was so warm and forgiving as they learned how to parent a teenager.

“We went from a two-year-old learning to use the potty to teens and cell phones,” Rob Gerlach quipped. “We’re making this up as we go along.”

But being good parents doesn’t require accolades or expertise, just a willingness to love and support a child who has been through a rough past, said Mike Hamblin, director of Foster/Adoptive Family Recruitment for Utah Foster Care.

“(Foster parents need) the ability to have patience and love for a child,” he said, “To give them the opportunity to learn and to grow, understanding they’re coming from a different background, and they’ll make mistakes as they get stabilized.”

Different paths to foster care

Most children enter the foster care system because it has been deemed unsafe for them to remain in their homes, either because of abuse or neglect.

After an initial removal, caseworkers try to place the child with a relative, but if that’s not possible, the worker will look for an appropriate foster family, Hamblin explained. If one can’t be found immediately, the child will go to a shelter, like the Christmas Box Houses or a boys or girls group home, while they continue to wait for a foster care family.

At this point, the clock is running on a 12-month window for the child’s biological family members to resolve their problems so the child or children can safely come home.

Reunification is the initial goal for nearly all children and teens, Hamblin said, yet state statistics show that only 39 percent of children return to biological parents or primary caregivers, while another 15 percent are placed with other relatives.

When reunification isn’t possible, the state works to create a permanency plan for the child, whether it’s adoption by a foster-care family or custody and guardianship.

“The state is trying to avoid having kids “age out” of foster care,” Hamblin said. “The permanency plan (gives them) a connection to an adult, a mentor whom they can refer back to as they go through life.”

Such connection is crucial, officials say, citing national statistics that show children who “age out,” — turn 18 and become legally independent — are more likely to experience unemployment, early pregnancy, homelessness and incarceration than their peers who were not in foster care. In 2010, 203 teenagers “aged out” of Utah foster care system.

Doe Corrin has definitely seen the impact of a stable home on her 16-year-old foster daughter, who was too shy to tell the group herself, but wanted her mom to convey how much she appreciates rules and structure – things that were missing in her biological home.

“I didn’t have to go to school before,” the girl quietly added. “(Now), it’s not that they’re making me, I want to do it because I don’t want to be a nobody when I get older. I feel like a somebody now.”

The need for foster families

The path for foster parents is also lengthy, but less emotionally draining.

First, interested individuals, who can be single or married, fill out an online form to request a consultation with a Utah Foster Care staff member in their area.

During the initial consultation, the staff member will meet with the individual or parents in their home and explain the expectations and answer any questions, according to the Utah Foster Care Foundation website.

If becoming a foster/adoptive family is a good fit, the family begins their home study paper work, which is a detailed report about themselves and their children, if applicable, including background checks, medical reports and reference letters.

Potential foster-parents must also complete 32 hours of training before they can be licensed and begin receiving “placements” or foster children.

It may seem like a complicated process but there’s plenty of help along the way, the parents attested.

“I’m astounded at how many resources are out there and how many people have dedicated their lives to helping people,” Rob Gerlach said.

It’s not always an easy process, and there are difficult days and trying experiences, but the parents on the panel said they’ve loved learning from their foster teens.

“I think foster kids are amazing to deal with adult stuff at such a young age,” said Doe Corrin. “They’re tough little cookies. They give to your life as much as you give to them.”

Although foster teens often get stereotyped as troubled individuals, Hamblin clarifies that they’re “pretty normal kids, but the difference is they’re in a stressful situation, they’ve experienced trauma and they’re not living with families.” Such a factor of combinations would be a struggle for anyone, he said.

And while delinquency may be a factor for some of the teens, much of it ties back to the environment they were in before, not necessarily serious behavioral issues, he said.

“Until you get to that point where you take a child in, there is that fear,” said Cody McBride, on the Division of Child and Family Services Program Manager Resource Family Consultant Team for the Salt Lake Valley Region. “But once they come into your home, you see they’re amazing kids. And they have an opportunity, in many cases, to be who they’ve always wanted to be.”

For more information call 1 (877) 505-5437 or visit www.utahfostercare.org/index.php

e-mail: sisraelsen@desnews.com

What Foster Parents Need to Remember:

Every child is different. Some open up quickly while others take more time to feel comfortable in a foster home.

The child may not come in filled with gratitude – after all, they’ve just been pulled away from their family, friends and potentially their school.

Some children may not want to be adopted, but perhaps custody and guardianship may be a possibility

Biological family ties are still important to children, and they may need your help to stay in contact with siblings, parents, grandparents, etc.

Just because a child came out of a difficult background doesn’t mean they are bad kids or need millions of rules. Get to know the child and what they need.

There are no perfect kids, whether they’re biological, adopted or foster kids. And there are no perfect parents.

Sources: Utah Foster Care Foundation and parent panel